Knowledge Networking Portal for Sustainable & Responsible Tourism

From Hurghada to the Wadi el Gemal: Egypt's Unsustainable Path in Tourism Development

From Hurghada to the Wadi el Gemal: Egypt's Unsustainable Path in Tourism Development

By Gordon Sillence, 4th March 2025

International Sustainability Consultant and ICT Director Tourism 2030 Sustainability Portal

to be released for ITB 2025 to remember the 'Spotlight on Unstustainable Tourism Rusty Nail' Awards ten years ago and in doing so honour the work of Valere Tolle to create a community of tourism stakeholders standing up for fragile ecosystems and preserve them through genuine nature-first ecotourism development. Please read on ...

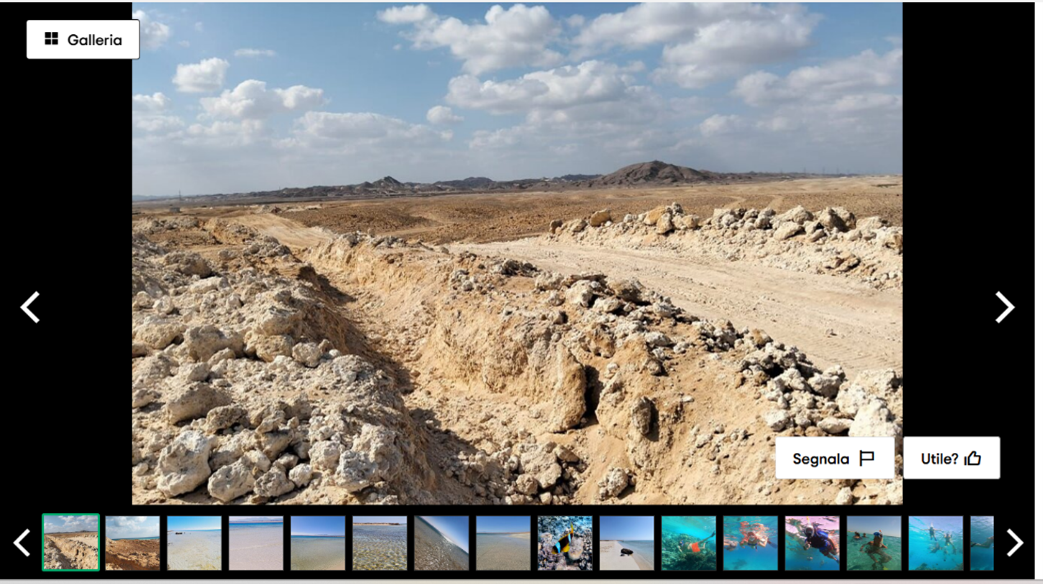

Tourism property development in the Middle is has become a hot topic since the announcement of the Gaza Riveira to be built on the bones on Palestinian children, but the dark side of unregulated resort development in pristine protected ecosystems is decades old and now reaching the farthest corners of the earth. This report emphasizes the need for transparent sustainable tourism planning policies to prevail over rapacious property development, especially in fragile habitats, using the degradation of Hurghada in Egypt as a critical example to highlight the urgency of protecting the Wadi el Gemal National Park from a similar fate at Ras Hankorab, where bulldozers are currently destroying the beach ecosystem in yet another unsustainable tourism development that should be stopped though Egypt’s good governance of the protected area.

Introduction

Introduction

Whilst we see geo-political crisis after crisis accelerating Global Change on the front pages of mainstream media, the real crisis is at the local level, where the talons of US driven international capitalism rip though the fragile fabric of local biodiversity in the name of property development, international luxury tourism and resource acquisition.

This article echoes the call of the Ahmed Al-Daroubi, Global Campaigns Director, Climate Action Network, who has pointed out the current wrecking of a precious Red Sea coral beach habitat in the latest questionable round of Egypt mass tourism development.

‘The importance of the Red Sea beaches is local and global. The importance of the Egyptian Red Sea is not limited to those who live on its shores, but as the severity and frequency of the effects of climate change increase, its protection has become a global priority. Studies have shown that the coral reefs in the northern Red Sea are the most naturally resilient to the climate crisis, with current projections indicating that 90% of coral reefs around the world will be functionally degraded by 2050. Since coral reefs support more than 25% of the world’s marine life and are directly dependent on by about a billion people, they are essential to protect in the northern Red Sea as they are the last remaining reefs—and they may be the source of the planet’s reef regeneration. It would be insane to build or develop in the few protected areas we have along the coast.

In particular, Ras Hankorab is a shared public space, with hotels throughout Marsa Alam and beyond offering day trips to the beach as a tourist attraction open to all.’

Unsustainable Tourism in the Red Sea – the Horror of Hurghada

I was in Hurghada/Egypt on the Red Sea seven years ago writing about the massive negative impact of tourism on their beautiful coral beach environment, and warned then that this type of rapacious tourism development would move to the less populated south, where the desert meets the coral sea beauty of Egypt’s Wadi el Gemal National Park. Here a(nother) pristine beachscape has suffered the first incursions of mass tourism.

For those familiar with Egypt’s tourism industry, this tragedy evokes troubling comparisons to the unsustainable developments that have ravaged Hurghada’s coastline and so many other pristine natural beach habitats being turned into tourism profit centres all around the world. With plans for a further 27 (!) resorts at the northern entry of the park, it is essential to re-affirm the need for juridical legal process to be the main conservation tool to protect fragile ecosystems, and to apply this key principle to the execution of national, regional and local development planning.

When I wrote seven years ago about the unfortunate likelihood of such developments spreading the still pristine south of Egypt, the now recent destruction in Wadi el Gemal bears alarming similarities to the environmental mismanagement mistakes in the face of commercial pressure made in Hurghada. At Ras Hankorab, heavy machinery has torn apart a pristine beach without full planning permission, violating the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) rules, which prohibit any groundworks before approvals are secured. Wadi el Gemal, celebrated for its ecological diversity and cultural significance, is now at risk of following the same unsustainable trajectory as Hurghada—a fate that Egypt, as a signatory to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), cannot afford.

Hurghada, once a haven for thriving coral reefs and diverse marine life, is now a cautionary tale of unchecked tourism development. Over the past few decades, sprawling hotel resorts and tourism infrastructure have obliterated natural habitats, damaging the very ecosystems that once attracted visitors. Coral reefs—critical to marine biodiversity and local livelihoods—have been decimated by unregulated construction, pollution, and over-tourism. This environmental degradation has reduced Hurghada to a shadow of its former ecological self, threatening its long-term viability as a sustainable tourism destination.

The Current Local Tourism Crime Scene – The Rape of Ras Hankorab

At Ras Hankorab, also known as Sharm El Louly, the idyllic natural beach environment has been scarred at the end of 2024 by a hotel concession who is currently bulldozing the site boundaries of a yet to receive planning permission development. This in direct violation of environmental regulations laid down in the GSTC criteria, ignoring the principles of sustainable development and global commitments to biodiversity protection in processes such as the UN CBD, who ought to have a procedure in place by now to deal with these transgressions.

Both cases reflect systemic failures in environmental governance. The Law of Sustainable Development (DG Environment 2000) which has a main principle that requires the preservation of fragile habitats, has been sidelined in favour of short-term economic gain though tourism property development. Add the current military-driven structure of Egypt’s economy, which creates conditions where protected areas are sacrificed to private interests with little oversight or accountability.

The destruction of natural habitats for tourism infrastructure directly undermines three critical UN Sustainable Development Goals: SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). These goals emphasize the urgent need to protect marine and coastal ecosystems and to ensure that development does not come at the expense of ecological integrity, and as host of CoP 14.

The Need for Good Governance in the Era of Autocratic Authority

The example of Hurghada demonstrates the long-term consequences of prioritizing rapid development over environmental sustainability. While tourism profits may surge temporarily, the destruction of natural habitats ultimately diminishes the value of these destinations, driving away the very tourists drawn to their beauty. Wadi el Gemal is at a crossroads: it can either follow Hurghada’s unsustainable path or become a model for balanced, sustainable tourism development. The direction of development as ever depends on stakeholder interest and power.

The Egyptian conservation authorities must act decisively to prevent further environmental destruction in Wadi el Gemal and beyond. Conservation measures must be enforced by the correct environmental authorities, with strict penalties for violators. There has been a wealth of studies showing sustainability options for ecotourism development to support conservation of such sites, and more International sustainable development expertise should be leveraged to work with local authority staff guide tourism projects, ensuring they align with GSTC principles and the UN’s biodiversity goals. Crucially, local stakeholders—who have the deepest understanding of the environment—must be empowered to manage resources and participate in decision-making. The interests of external property development plans must be made transparent and agreed by local stakeholders.

Hurghada’s degraded coastline serves as a stark warning of what happens when economic interests override ecological responsibility. Wadi el Gemal must not become another cautionary tale. By adopting a model of sustainable, community-led development, Egypt can protect its irreplaceable natural heritage – while still reaping the economic benefits of tourism. The time to learn from past mistakes is now—before another of Egypt’s ecological treasures is lost forever.

For further information:

- https://www-shorouknews-com.translate.goog/columns/view.aspx?cdate=27022025&id=6bb52c85-7ba8-4db3-b4a8-238fe62573a4&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=it&_x_tr_pto=wapp

- Ahmed Al-Daroubi Global Campaigns Director, Climate Action Network

- See also TripAdvisor: https://www.tripadvisor.it/ShowUserReviews-g311425-d2703875-r991494333-Sharm_El_Luli-Marsa_Alam_Red_Sea_and_Sinai.html

Contact: gordon.destinet@ecotrans.de

|

|

|

| Address | |

|---|---|

| Target group(s) | Governments & Administrations |

| Topics | Destination Management , Good Governance & CSR , Natural Heritage & Biodiversity |